Skill Acquisition and Biomechanics for Physical Educators Blog

MAJOR QUESTION: What biomechanics are involved to ensure optimal technique of maximal accuracy and distance with a driver off the tee in golf?

The primary goal of using a

driver in golf is to hit the ball as far and as accurate as possible and to

land the ball on the fairway, this sets up the next iron shot (Hume, Keogh

& Reid, 2005). A successful drive in golf can set the hole up for a

par, or below for a golfer. A driver is predominately used for hitting the

ball long distances as it can utilise a greater range of motion and

larger forces then any of the other clubs in a golf bag. The mechanics of a golf stroke include

five phases; these are as follows; the set-up, the backswing, the downswing,

the impact and the follow through (Keogh & Reid, 2005). The optimal

technique throughout these phases of the ideal golf swing can help to

improve overall performance of distance and accuracy and also reduce the

risk of serious injuries related to golf (Keogh & Reid, 2005).

Momentum is defined as the product of mass (matter of object) and

velocity (speed in a given direction), or measure of motion composed by a

body (Blazevich, 2007; McGinnis, 2013). The larger the mass of an object

and the more momentum it has, the larger the force will be created when

the club head hits the ball on impact (Blazevich, 2007). Momentum plays a

huge role in the swing phases of the tee off in golf. This transfer

of momentum is evident through a professional golfer when the correct

technique is performed by them at tee off. The tee off with a driver in golf

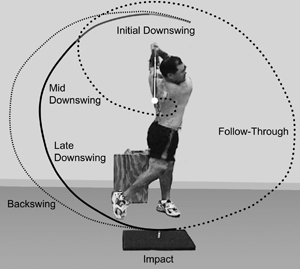

can be broken down into four major swing phases, plus a set up of shot and

preparation of stance phase. These four stages are; the backswing, the

downswing, the impact and the follow through (see figure 1).

Figure 1: This illustration shows

the four swing phases of the tee off with a driver in

golf. A smooth transition between phases enables a successful shot

that has distance whilst maintaining accuracy to be played.

SET UP- PREPERATION

The posture and alignment must be addressed correctly

to set up before the swing of the golf club occurs. Firstly the stance must be

focused on, the golfer must take into consideration balance and posture (Maddalozzo, 1987). If a golfer has

their feet positioned to close together they may find it difficult to turn

freely and to their fullest extent (Maddalozzo,

1987). If a golfer positions their feet too far apart they may find it

to hard to generate enough maximum force, through prohibiting the necessary leg

drive that is needed to power the ball (Maddalozzo, 1987). Therefore, the golfer must spread their feet

approximately shoulder width apart (refer to figure 2) (Maddalozzo, 1987). The golfers’ centre of

mass should be evenly spread over both feet during this stance as well (Kawashima, 1994). This can allow

for production of energy to be maximised when transferred through the body, to

the club and onto the ball (Kawashima,

1994; Maddalozzo, 1987). The golfers left arm must be straight while the

elbow must be slightly bent on the right arm (refer to figure 2) (Maddalozzo, 1987). A straight left arm ensures

the golfer is able to increase the speed and range of motion of the club head (Maddalozzo, 1987). The bending

left arm assists in decreasing the risk of delivering the club head outside of

the target (e.g. the teed golf ball) (Maddalozzo, 1987). The golfers head must also be directly over the

top of the ball to ensure that the eyes are focused on the target (the ball)

(refer to figure 2) (Maddalozzo,

1987).

Figure 2: This diagram shows the preparation in

order to execute a tee off shot with a driver in golf. The three things

highlighted (by numbers) are the stance, head position and arm positioning;

these things are important for balance and posture before commencing the skill.

The main purpose of the

backswing is to position the club head so that the golfer can execute an

accurate and powerful downswing (Hume, Keogh & Reid, 2005). By doing this

it stretches the golfers’ muscles and joints in charge of generating the power

behind the shot (Hume, Keogh & Reid, 2005). The first movement of the

backswing involves a backwards and upwards motion of the club head, the torso

also rotating to the direction of the club, which in this case is to the right (Chu Chu ,

Sell & Lephart, 2010). The left knee is also rotating as are

the hips and this is done in one single motion (refer to figure 3) (Chu Chu Chu

Figure 3: This image shows the

backswing of a golfer at a tee shot at its highest point just before commencing

the downswing. Here it is visible to see the rotation of the torso, and knees whilst

the hands are above the eye line.

The purpose of the downswing is to return the club

head to the ball on the right plane with maximum velocity provided from the

backswing and downswing (Chu Chu ,

Sell & Lephart, 2010). This acceleration from the top of the

backswing to the impact of the ball generally takes between 0.02-0.10 seconds (Myers et al., 2008). With the

initiation of the downswing the body weight shifts from the trailing foot at

the top of the swing towards the leading foot (refer to figure 4) (Hume, Keogh

& Reid, 2005). The angle of the wrists should return back to a normal

un-hinged state just before the impact on the ball and it is said that this

contributes significantly to club-head velocity (refer to figure 4) (Chu, Sell & Lephart, 2010;Hume,

Keogh & Reid, 2005). The power produced by the legs in the downswing plays

a major role in the drive for a golfer. This kinetic energy then moves up

through the arms and provides the necessary power for the acceleration of the

club head (Blazevich, 2010; Chu

Figure 4: This image shows the downswing of the

golfer at a driving tee shot, from its highest point down to just prior to

making contact with the ball. It is clear to see the transfer of weight between

the top of the downswing to the bottom of it.

THE IMPACT

The aim of the impact is to strike the ball flush

with the club-head at maximum velocity produced during the backswing and

downswing (Hume, Keogh & Reid, 2005). At impact the right-handed golfer

should have the majority of their body weight onto their lead-foot (refer to

figure 5) (left) (Maddalozzo, 1987).

The wrists also need to be straightened to enable them and other body parts to

produce maximum force upon the ball (Maddalozzo, 1987). It is also important that the hands are

positioned in line with the club head or slightly ahead of it on impact (refer

to figure 5) (Hume, Keogh & Reid, 2005). By moving the weight of

the body forward, this is creating momentum which can be transferred from the

body, down the shaft of the driver and onto the club-head, this then travels onto

the ball once impacted (refer to figure 5).

Figure 5: This illustration compares the set-up and

preparation phase with the impact phase, the majority of weight is placed on

the lead foot on the right-hand side (impact phase).

THE FOLLOW-THROUGH

The main purpose of the follow-through is to

decelerate the momentum built up from the body and the club head during the

backswing, downswing and impact; this is done by using eccentric muscle flexion

(Hume, Keogh & Reid, 2005). During this phase both shoulders rotate

forwards towards the direction the ball has been struck (refer to figure

6) (Hume, Keogh & Reid, 2005). When the hands reach shoulder level

both the elbows flex to decelerate the speed at which the arms are moving and

the torso rotation (Hume, Keogh & Reid, 2005). As the torso and hips rotate

the majority of the body weight is now planted on the left leg and it rotates

outwards to absorb this load (refer to figure 6) (Hume, Keogh & Reid,

2005). To finish off the follow through, the golfer must be in a balanced

position with the torso and head facing the direction the ball is travelling in;

the hands should also finish behind the left ear (refer to figure 6) (Hume,

Keogh & Reid, 2005).

Figure 6: This diagram shows the follow-through of

the golfer at a driving tee shot, from just after impact until the completion

of the follow-through.

MAINTAINING ACCURACY ON A GOLF BALL

Maintaining

accuracy as a golfer at a driving tee shot is very important, if achieved and

the ball lands on the fairway this sets ups the next iron shot with increasing the

chance at making the green in regulation. Once a ball has been struck, it may

start off in a straight trajectory but then veer off to the left or right (Libkuman, Otani & Steger,

2002). In golf, veering off to the right is generally known as a slice,

veering to the left is generally known as a hook. This is done so when

accidental spin is put onto the ball due to a slight pull or draw of the driver

face (Libkuman, Otani

& Steger, 2002). This spin affects the golf ball moving through the atmosphere,

as one side of the ball is grabbing the air, this causes higher friction

between the ball and the air (refer to figure 7)(Blazevich, 2010). These particles in

the air then start to spin the ball causing one side of the ball to slow down

whilst the other side still moves freely (refer to figure 7) (Blazevich, 2010). This slow

moving air on the one side of the ball forces it to swing away from its

intended straight trajectory and is known as the Magnus effect (refer to figure

7) (Blazevich, 2010). A

professional golfer who has had coaching and understands that they may have a

natural hook or slice can then alter their club head grip and/or technique to

combat this (Ming &

Kajitani, 2003; Chu , Sell & Lephart,

2010). A higher grip on the golf club generally means a longer lever is

created and can generate greater velocity, but control may be lost (Chu Chu

Figure 7: This image shows the Magnus effect when

the ball is in flight after it has been struck. It is clear to see

the friction the ball has on one side which causes this unwanted spin to

occur.

MAXIMISING DISTANCE ON A GOLF BALL

The golf swing consists of several biomechanical

principles, one of these is the ability to maximise the force, this transfers

into distance. The three Newton

‘An object will

remain at rest or continue to move with constant velocity as long as the net

force equals zero’ (Blazevich, 2010, p. 44). Inertia is present in every object

containing mass; therefore it will remain in its current state unless an

external force is applied to it (Blazevich, 2010). Force can be defined as ‘the

effect one body has upon another’ (Nesbit&

Serrano, 2005). In terms of a golfer hitting a ball off the tee with a

driver, this happens when the club strikes the ball causing an impact. The

force transferred from the club head onto the golf ball’s inertia disrupts it

from its current state. So in theory the more force striking the golf ball the

longer distance it should travel (Chu

‘The acceleration of an object is proportional to the net force acting on it and inversely proportional to the mass of the object’ (Blazevich, 2010, p. 45). To change an objects state of motion, an external force must be applied to it. This means that the less mass an object has, with force, the faster it will accelerate (Blazevich, 2010) Acceleration can be defined as ‘the rate of change of velocity’ (Blazevich, 2010, p. 7). Applied to a golfer who is teeing of with a driver, this increased momentum of the club head by the muscles and joints produces greater acceleration of the club head before the impact on the ball (

‘For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction’ (Blazevich, 2010, p. 45). This recognises that if a force is placed on an object, an equal and opposite force known as a reaction will be placed on that object that has created that initial force (Blazevich, 2010). This affects a golfer who is teeing off with a driver when they strike the ball; on impact this energy projects the ball forward. There is also a reaction from the ball on the club-head and up the shaft, completing a proper follow through allows energy to be transferred into this reduction of momentum by flexion of the joints and muscles within the body (Hume, Keogh & Reid, 2005).

ANSWER:

When analysing the tee-off with a driver it is important to break the

skill down into certain phases to achieve maximum distance whilst maintaining

accuracy of the shot. The four swing phases include; a backswing, downswing,

impact and follow through with set up and preparation phase also being important

for the shot. All of these swing phases are just as important as the other and

should be completed sequentially. If one or more of these phases are not completed

smoothly with the optimal technique it may lead to poor contact with the ball;

this may mean it does not travel in the desired direction. The

angle of the club-head is vital to; if it is slightly off the Magnus effect

will take hold of the ball so it will veer off of its intended course. Some

debate still remains on what the optimal biomechanical techniques are to assist

golfers when they tee of for maximum distance whilst maintaining accuracy.

However, it is suggest that golfers’ practice their own techniques as to what

may work best and what is successful for them, by following the biomechanical

principles stated.

HOW ELSE

CAN WE USE THIS INFORMATION?

The biomechanical principles of the drive in golf

can be applied to many other sports. In baseball and cricket a similar

technique can be seen as the momentum of the muscles and joints transfers into

force when the bat strikes the ball (object). This information gained from

biomechanics can assist in fine-tuning techniques, especially for professional

athletes who strive for any edge over their competition. It is also important

that these optimal techniques are established by professionals’ healthcare

workers to assist both amateur and professional sportspeople in preventing injury.

This knowledge also assists professional educators such as teacher or coaches,

who may want to improve technique or to be supported in explaining where individuals

may be struggling within the skill.

REFERENCES:

Hume, P., Keogh, J., & Reid, D. (2005). The

Role of Biomechanics in Maximising Distance and Accuracy of Golf Shots. Sports

Medicine, 35(5), 429-449.

Kawashima,

K. (1994). Comparative analysis of the body motion in golf swing. Journal Of

Biomechanics, 27(6), 672.

Keogh, J., & Reid, D. (2005). The role of

biomechanics in maximising distance and accuracy of golf shots. Sports

Medicine, 35(5), 429-449.

Libkuman, T., Otani, H., & Steger, N. (2002). Training in Timing

Improves Accuracy in Golf. The Journal Of General Psychology, 129(1),

77-96.

Maddalozzo, G. (1987). SPORTS PERFORMANCE SERIES:

An anatomical and biomechanical analysis of the full golf swing. National

Strength & Conditioning Association Journal, 9(4), 6.

McGinnis, P. (2013). Biomechanics of sport and

exercise. Champaign , IL

Ming, A., & Kajitani, M. (2003). A new golf swing robot to simulate

human skill––accuracy improvement of swing motion by learning control. Mechatronics,

13(8-9), 809-823.

Myers, J., Lephart, S., Tsai, Y., Sell, T.,

Smoliga, J., & Jolly, J. (2008). The role of upper torso and pelvis

rotation in driving performance during the golf swing. Journal Of Sports

Sciences, 26(2), 181-188.

Nesbit,

S. M., & Serrano, M. (2005). Work and power analysis of the golf swing. Journal

of sports science & medicine, 4(4), 520.